The incarnation works in 2 directions – it is a break-in and a break-out. God breaks into our world, like an asteroid, leaving a crater and changing the atmosphere. This sounds dramatic, but it is not easy for but we have to grasp the scale of what has happened. We get on with our little lives, the Church gets on with its little life, and we are tempted to think we can set it up as we lie it. Karl Barth has said the Church’s life is a … crater formed by the explosion of a bomb, and the Church seeks to be no more than a void – in which God reveals himself. We are to get out of the way, in other words, for God is sovereign. The second significance of the incarnation is in the other direction – we are broken out of our world. Christ comes like the angel to Peter in prison, smites him on his side, and shows him the open door. We all live in a bubble – the bubble of our particular life. It’s the same for every human being, from the poorest of the poor to Prime Ministers and presidents. All the lot of us each lives the bubble that surrounds us. Christ’sincarnation is about our breaking out from our bubble.

Jesus comes to a wedding at Cana into Galilee – here he is at a nice domestic event with good folk innocently enjoying themselves. They run out of drink and he saves the day, stocking up the bar. It’s easy to see here a nice, homely human setting for Christ’s first tentative revealing of himself. But apart from his mother, his glory is only revealed to the servants who see the miracle happen. Everyone else at the feast is ignorant of what has come about. But the servants, you can be sure, will have talked no end afterwards, and everyone will have got to know, and been mystified and feeling a certain sense of awe. This happening is no low-key tentative event – it is the first sign that their world, and ours, is being blown apart.

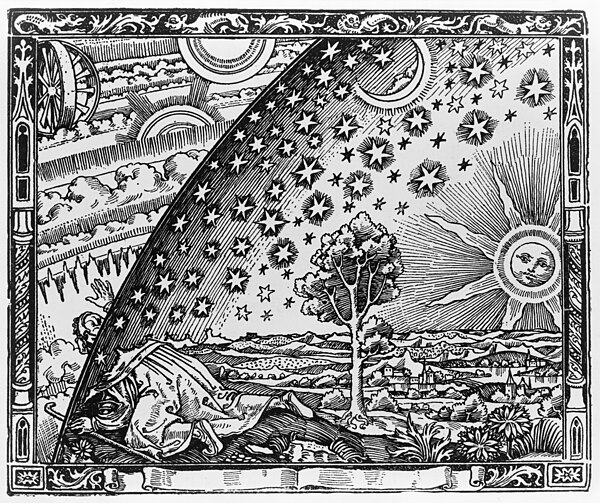

I like the illustration on the back of your hymn sheets, and hopefully it’s appearing too on your screens. The authorship and origin of this engraving are disputed, and there are many theories on what it is supposed to be depicting. There is a beautiful Earth with the beauty of the sun and the stars in the dome of the firmament. And at the left a man on his knees in some astonishment, as his head gets through the dome and he sees an amazing world beyond. This can obviously be seen as a paradigm of prayer, where the praying man or woman sees beyond the ordinary and the familiar and into the mysteries of God. At the top left there is a great double wheel – you will remember that the prophet Ezekiel had a vision of God riding upon great wheels – is this Ezekiel? Or is the man simply seeing the wonders of God, symbolized by the wheels of that Prophet from the past? Another possible explanation also fits well – before modern times people believed the sky was a dome that met the Earth somewhere beyond the horizon. There is a mediaeval story of a monk who travelled to the edge of the dome of the sky, to the point where it meets the Earth. As the dome came lower and lower his head eventually went through it, and he saw into heaven.

Whatever the original artist intended, I find this picture very helpful in reminding me that the world I see around me, and all my concerns, and the way I see things, are all in a bubble, my view of things is very limited. I need Christ in his incarnation and epiphany to train my eyes beyond, so that my picture of things can be transformed.

We must be careful here – this is not about leaving our life behind. It is not suggesting a division between earthly life and the life of heaven, or that we should try to leave life behind in our quest for heaven. The miracle at Cana makes clear that for us earth and heaven go hand-in-hand. God’s glory is revealed in everyday life. That’s difficult for us – it’s difficult to remain aware that the whole of life is an epiphany, with Christ present in everything around us waiting for us to see. Christ calls the fishermen to leave their nets and follow him, but what they follow him into is the hurly-burly of life, not away from it, and we are told that they also carried on fishing.

Similarly in the Church: in the liturgy, the Scriptures, our daily prayer, we are coaxed out of the bubble of our daily life, not to leave it behind, but to bring it with us, but in the process we negin to see daily life differently.

In particular we are warned against domestication. Domestication of our lives, domestication of Christianity. When we domesticate the gospel we fill up the crater left by Christ’s bomb with stuff that we like. Christ shows us that our emptiness can only be filled by the God who is sovereign over all things, God who often gives us what we weren’t wanting. The French writer Paul Claudel speaks of God as a difficult lodger who moves furniture around, knocks nails in the walls, and even breaks up the furniture in order to light a fire. In monastic life it certainly feels that God is like that, breaking up our such-nice furniture all the time. It’s the case also in a residential theological College – we are challenged beyond our domestic bubbles – the bubbles bounce into each other, and divine grace enables a miracle whereby the bubble doesn’t go pop but gently opens up. In our parishes as well Christ is waiting to reveal his glory: in the Scriptures, in the liturgy, in our prayer, and in the people. Only Christ can lead us all out of domestication and towards himself.

St Benedict says in the Prologue to his Rule: “do not immediately be dismayed and run away in fear from the way of salvation, whose entrance must necessarily be narrow.… But as we advance … Our heart will be enlarged”. This is a journey from being small to being enlarged.

You might think that the talk of explosions, craters and difficult lodgers is a bit macho – God however is not macho – God is love, love that is crucified. Not for itself, but for us. Surprisingly, this bomb, this explosion, is for our peace. It is for

the póor in spírit

thóse who mourn,

the meek,

the mérciful,

the púre in heart,

the péacemakers,

We need to be helped out of ourselves. The only thing that will do this is Christ’s glory, made manifest in the the incarnation, crucifixion and resurrection, and manifested too in the people around us, if only we will see. And this glory is not far below the surface in what happened at that wedding.